- Spitfire News

- Posts

- AI-generated influencer scandals are here

AI-generated influencer scandals are here

Now anyone can play with the hyperrealistic likenesses of public figures.

Content warning: This article discusses an influencer with a severe eating disorder and may be triggering to some readers.

I was searching for a specific video clip of the influencer Eugenia Cooney last month when I stumbled upon something very strange. I found what I was looking for—supportive comments she had made previously about Donald Trump—on a YouTube channel dedicated to archiving clips of her. But in addition to documenting her TikTok livestreams, this channel had also begun posting clips of Cooney that were labeled as being AI-generated.

Cooney is an extremely polarizing influencer, mainly due to her highly-publicized struggle with a severe eating disorder. Her look is instantly recognizable: heavy, colorful MySpace-era makeup, complete with thick winged eyeliner. Gothic, skimpy, girlish outfits. And she’s alarmingly thin. These attributes have stoked a lot of outrage and concern, which Cooney has parlayed into massive social media success. She’s frequently among the most-watched people on TikTok Live.

She will also take occasional breaks from posting content altogether, which tends to drive conspiracies about her health and whether she’s even alive. Her most recent absence, combined with the now-ubiquitous generative AI tools at anyone’s disposal, have created an opportunity to fill the void of real Cooney content with AI-generated Cooney content. And that content is truly bizarre.

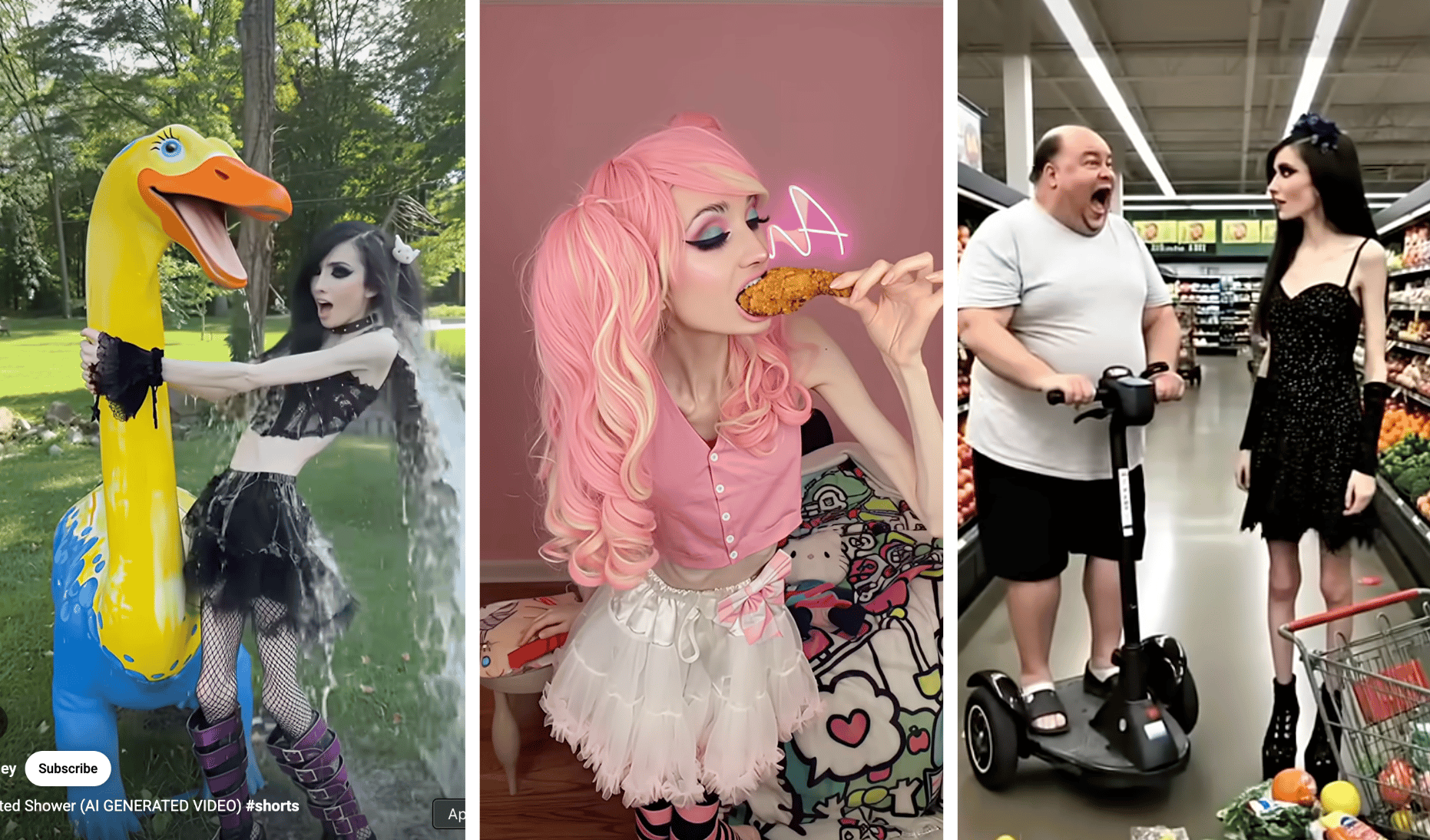

Over the past several weeks, the YouTube channel I stumbled upon—which has nearly 250,000 subscribers, making it potentially quite lucrative—has posted dozens of AI-generated videos of Cooney in replacement of its typical updates. These are clearly labeled as AI in video titles and descriptions, so they don’t immediately appear to violate YouTube’s rules. But they are certainly cruel, offensive, and discomforting, sexualizing Cooney's likeness, showing her eating fried chicken, and juxtaposing her with (fake) overweight people on motorized scooters who scream at her, just to describe a few. The top comment on the fried chicken video says, “She'd lose it if she saw this.” Another comment says, “We can only see Eugenia Cooney eating through the AI generator.”

Screenshots of AI-generated videos of the influencer Eugenia Cooney, posted on YouTube Shorts by an account that typically archives real clips of her.

Like most AI-generated videos I’ve seen, the earliest slop posted by this channel had a disturbing, Cronenbergian appearance to it. AI images of bodies melded and morphed and shapeshifted in horrifying ways. But what’s even scarier is that in recent weeks, the Cooney videos have gotten… better. More realistic. Harder at first glance to recognize as AI.

It might not just be me. Both OpenAI and Google have released improved genAI video creation tools in recent weeks, and I’ve seen colleagues, friends, and, notably, lots of influencers contributing their own likenesses to their datasets. OpenAI’s Sora has introduced this as a feature called “cameos,” where you can voluntarily upload your face and voice to make hyperrealistic videos of yourself—and let others use your likeness to make their own videos, too. A Sora developer at OpenAI actually teased Sora 2 with hyperrealistic videos of CEO Sam Altman shoplifting, which anyone can make with Altman’s cameo. This seems really shortsighted, unless they want the plot of Mountainhead to come true.

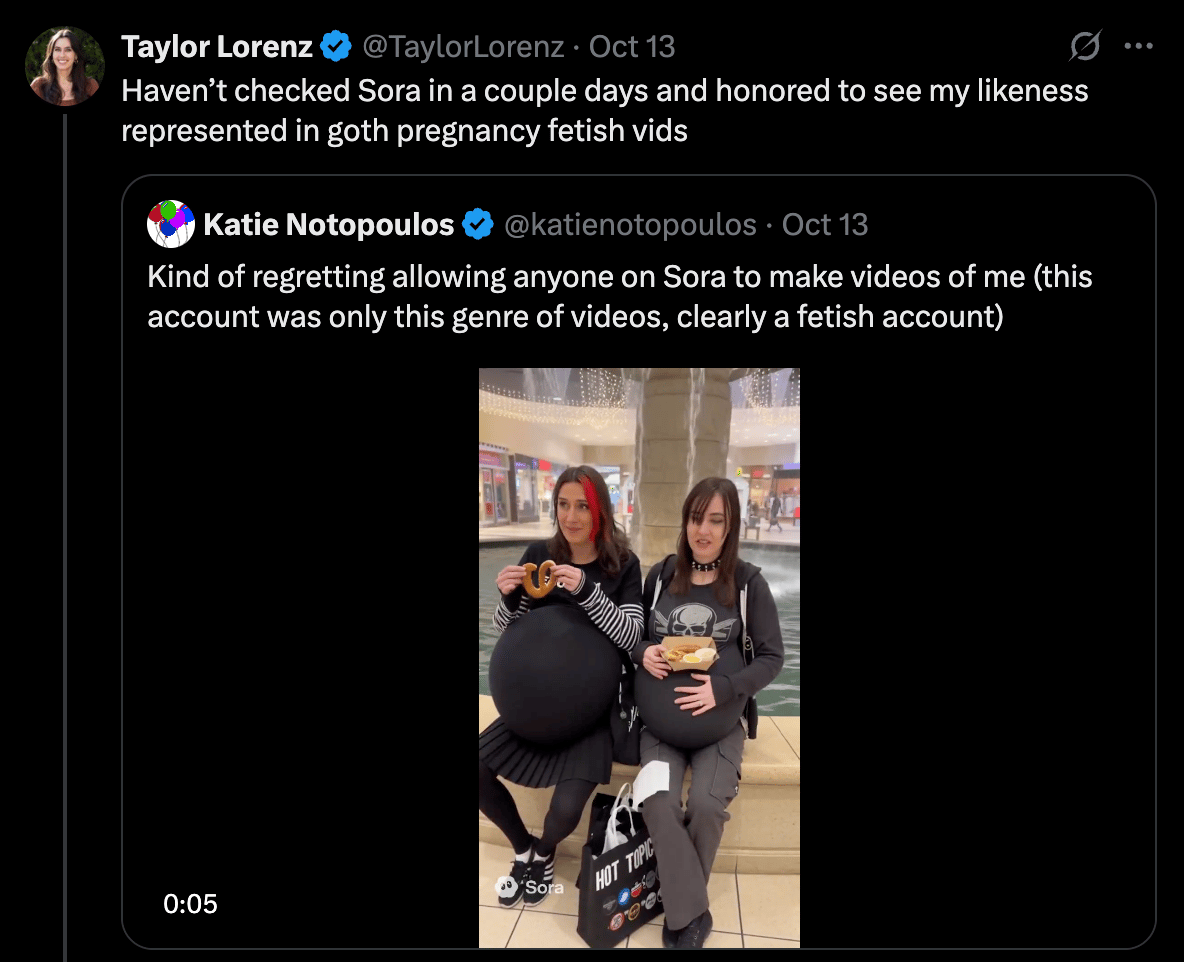

The controversial and highly annoying influencer Jake Paul, who is apparently a “proud OpenAI investor,” was tapped as the “first celebrity” to advertise the feature. Resulting AI videos of Paul made with Sora 2 had already been cross-posted to social media thousands of times and received over a billion views as of last week. According to the OpenAI subreddit, it’s mostly just Paul and his equally annoying little influencer friends who have taken advantage of the cameos feature. But some journalists have also tried it out, resulting in the likeness and voice of my friend Taylor Lorenz being used in AI-generated pregnancy fetish videos.

A screenshot of a post on X from Taylor Lorenz: “Haven’t checked Sora in a couple days and honored to see my likeness represented in goth pregnancy fetish vids.” Lorenz is quote-posting tech journalist Katie Notopoulos, who wrote: “Kind of regretting allowing anyone on Sora to make videos of me (this account was only this genre of videos, clearly a fetish account)”

The benefit of OpenAI’s cameos is that, at least in theory, you can delete unauthorized videos using your likeness. This feels like a loose safeguard—one that requires you to buy into and partake in the technology itself—to get ahead of the inevitable, which is that AI-generated videos already frequently place people’s likenesses (mainly women and girls) in nonconsensual sexually-explicit, suggestive, and offensive media. But like previous steps tech companies have taken to address this crisis of nonconsensual imagery, these safeguards put all the onus on victims to find, review, and initiate takedowns. It’s not practical and it doesn’t work on a grander scale. Advocates and victims say it can multiply the harm, not undo it. And it’s just OpenAI implementing this supposed safeguard, half-heartedly, after the fact.

Case in point: another one of my friends, the drama YouTuber Adam McIntyre, called me last week after discovering some crude AI videos of his likeness made by one of his online detractors. But these didn’t appear to have been created with Sora, so there was no opt-out possible. I examined the offender’s X profile and found he had also made a series of AI-generated videos of a private figure, inserting her likeness into videos of celebrity men who have been accused of sexual harassment.

“It’s disturbing, because I have no control over it, and I wonder about the intentions behind it. Do they just want people to see it and make fun of me?” McIntyre said when I spoke to him on the phone. “So then I wonder what prompts are being entered, and I wonder if they’re submitting photos of me and asking AI to alter them or if the AI already has a preset of what my face looks like because I upload so much content of myself.”

The embrace of generative AI technology by the masses typically follows this trajectory: first, it’s used to sexually harass famous women, especially influencers, because there’s already so much available media of them in existence online. The AI technology then becomes more sophisticated and widely available, so the tools are then used more widely to harass private figures—like girls in elementary schools. And of course, this all very profitable for (mainly) men, and, like all misogynistic violence, it reinforces their power. This is one of the key reasons I oppose generative AI: so far, it has overwhelmingly served to reinforce existing power disparities and forms of bigotry and violence in our society. Just like the research indicated it would.

Something AI researchers may not have expected is how AI-generated video output would quickly play a role in influencer scandals—the very online news stories that someone like McIntyre covers on his own YouTube channel. Taylor Lorenz wrote a good piece this week for User Mag about the smear campaign against Hasan Piker, the leftist Twitch streamer who has been repeatedly false accused of using a shock collar on his dog. There have been a slew of viral AI-generated clips of the dog attacking Piker and of Piker shocking the dog.

“Bad actors who are already comfortable manipulating real footage will begin fabricating videos of their targets or subtly altering them,” Lorenz wrote. “AI will also make it easier to search, catalog, and weaponize every video ever recorded. Finding all available clips of someone making the wrong hand gesture, or wearing a specific color, or moving their body in a certain way could be as easy as clicking a few buttons.”

An AI-generated video of Twitch streamer Hasan Piker’s dog electrocuting him has nearly 4 million views from just one X post.

Even if people don’t believe or trust this AI-generated video content of influencers and other public figures, some people will, because a lot of people already really struggle to identify when media is AI-generated and it’s constantly getting harder to tell. And even fake media can be part of a bullying or smear campaign.

One of the most notable cases so far of AI-generated influencer drama is happening in the U.K., where a notoriously homophobic influencer named HS Tikky Tokky (I hate it here, too) has referred to people “defaming” him with videos that show him applying makeup and acting flamboyantly gay. He said that his own family members have called him to ask about the AI-generated videos, not realizing they aren’t real. At first it may seem like internet comeuppance for being hateful, but as McIntyre explains, this still punishes the LGBTQ community.

“Marginalized people are still the butt of the joke,” he said. “The joke is not really on the creators, the joke is a stereotype about being flamboyant. And I think that straight men are able to weaponize AI in a way that women and other minorities can’t, because the demographic of people who use AI to create this stuff is usually edgelords.”

“Edgelords” are typically young men who create trollish, offensive, provocative internet content—someone like Jake Paul or Mr. Tikky Tokky. They may express outrage over their AI-generated portrayals, but it’s tongue-in-cheek. Paul has made tens of millions of dollars off other people hating him, because he can leverage his privilege to turn it into money and power. Sort of like Donald Trump, who is already frequently depicted in AI and is a big supporter of the industry. Before his re-election, Trump cheerfully discussed AI’s potential, alongside its ability to make convincing fake Trump endorsements, during an episode of Jake’s brother Logan Paul’s podcast.

Adam McIntyre signs posters for fans at a live show in Dallas, Texas in February 2025. (Photo by Kat Tenbarge)

As someone who covers influencer drama for a living, McIntyre told me he’s concerned that AI influencer drama will usurp authentic coverage, both in the subject matter of the stories and in the production of videos about them. I’ve already seen this happening with regards to celebrity news coverage on YouTube. AI channels can pump out AI videos about AI topics, and the CEO of the Instagram page The Shade Room told me in January 2024 that her audience was already struggling to tell the difference between fabricated and real celebrity news.

It kind of seems like we’re past the point of no return, and the implications are staggering. And influencers are on the front lines of these cultural changes. As McIntyre puts it:

“In the past, the biggest fear as a content creator that people could do to you is they could Photoshop a tweet of you saying something problematic, but now they can put in a prompt, not even have to edit anything, and get a video of you saying any slur, any problematic thing. And it can get you detained, get your family members to believe it. It’s incredibly dangerous.”

Thanks for reading this far, and if you appreciate my independent reporting, please consider upgrading your subscription for just $5. Your support makes this work possible, and you’ll also get access to my paywalled stories. Until next time.