- Spitfire News

- Posts

- Why I have to give Fortnite my passport to use Bluesky

Why I have to give Fortnite my passport to use Bluesky

Age verification laws are as ineffective as they are dangerous.

Before we get started, just a reminder that Spitfire News is currently having its first-ever SALE to celebrate hitting 10,000 subscribers! Get $10 off an annual subscription for a limited time! Or subscribe for free to get unpaywalled editions like this one.

I’m from Ohio, which means around this time every year I’m there for the holidays. And unlike in New York City, when I get on Bluesky in Ohio, I can’t access my DMs unless I verify that I’m an adult. I still get notifications that people are messaging me on the platform, which I use daily for work, but I can’t see what they’re saying unless I hand over part of my social security number, my credit card information, my passport, or my driver’s license to a subsidiary of the video game company that makes Fortnite. Yes, that’s right. I have to let Epic Games check my passport or other highly sensitive personal data in order to DM people on Bluesky when I’m at my parents’ house.

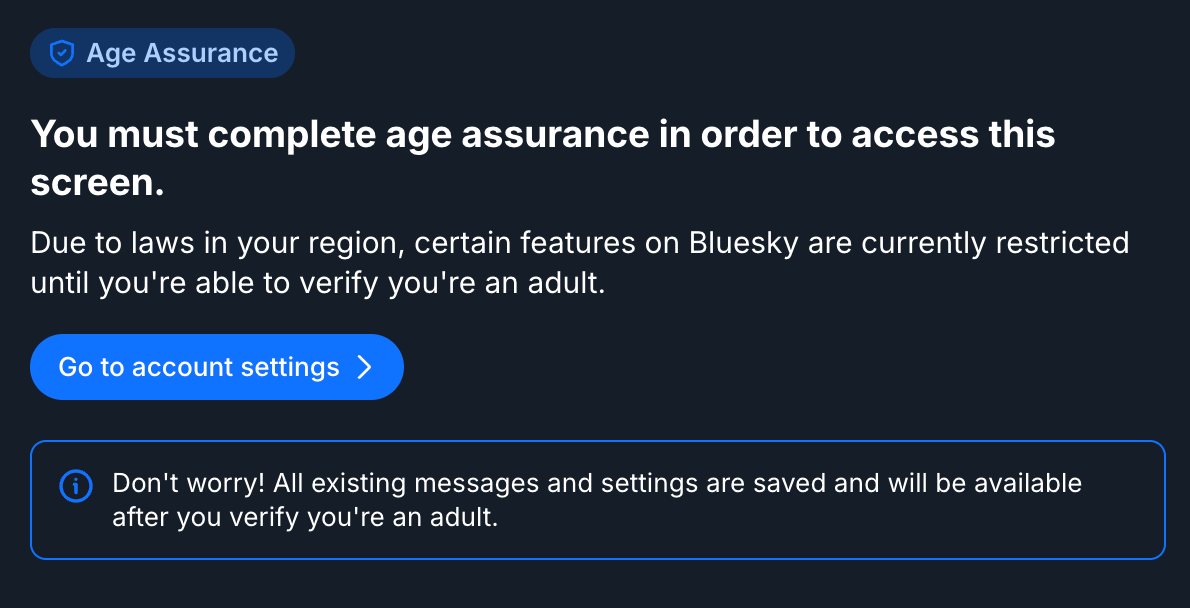

Here’s what that looks like on Bluesky.

A screenshot of my Bluesky app prompting me to “complete age assurance in order to access this screen,” Bluesky’s attempt to comply with age verification laws in Ohio.

Why is this happening? Well, to protect the children, of course! In late September, an Ohio law went into effect that requires websites that host content that could be deemed “obscene or harmful to juveniles” to block access using age-verification tools like the one owned and operated by Epic Games. This is supposed to target websites like Pornhub, which isn’t even complying, because the company doesn’t think the law applies to them as written. Ohio’s attorney general is threatening to sue them next year over it. But why would this affect Bluesky DMs? You can’t even send photos or videos over Bluesky DMs! Other platforms that are rife with obscene and harmful content, like Elon Musk’s X, have seemingly done nothing to comply with Ohio’s new law. And while the Bluesky community tends to lean pretty Gen X, it feels wrong that no one under 18 in Ohio could use the platform to reach out to, say, a journalist.

Therein lies just a few of the issues with age verification laws: they’re ineffective. They’re confusing. They result in nonsensical applications of law and missed opportunities to actually prevent minors from being exploited online. And finally, as much as I enjoy Fortnite (I don’t enjoy Fortnite), I don’t exactly trust a random Epic Games subsidiary with my ID. Shortly after Ohio instituted its law, a different age verification service was hacked and potentially exposed 70,000 government IDs belonging to Discord users who had submitted them to verify their ages.

Young people do have a right to speech and a right to information.

That information breach happened after the UK instituted sweeping new “child safety” laws to protect the kiddos. Because collecting and leaking your identity is surely going to keep them safe, right? Well, even if your data is safeguarded properly, the UK’s so-called Online Safety Act has already censored information pertaining to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, with the potential to restrict access to life-saving information for both kids and adults around topics like abortion, safe sex, and LGBTQ healthcare. And the potential benefit of these laws is often rendered useless by kids and teens finding loopholes like VPNs (which can make it seem like you’re accessing the internet from a different, less regulated location) and tricking the verification tools into thinking you’re older than you actually are.

But despite all these obvious and proven flaws in age verification laws, they are currently on the table for federal legislation in the U.S. And they’re backed by significant bipartisan support, even under Trump 2.0 and the goals of Project 2025, which explicitly plans to scrub trans and queer people from the internet by conflating them with pornography (Project 2025 calls for porn to be outlawed and its creators imprisoned).

“We don’t have consensus, politically, on what is appropriate for children. A lot of the things that are cited in Congress are around mental health or violence, but we also have lawmakers across the country who are saying that LGBTQ resources and racial justice education and talking about Palestine and seeking abortions are not appropriate for children,” said Sarah Philips, a campaigner with digital rights advocacy group Fight for the Future. “Young people do have a right to speech and a right to information.”

Not being able to access my Bluesky DMs during the holidays is annoying, but it’s not a serious threat to my wellbeing. What I’m more concerned about is how this legislative patchwork of age verification laws benefits the rapidly growing authoritarianism in the White House and conservative movements to limit freedom and rights to bodily autonomy across the world.

Last year, I reported on how the Kids Online Safety Act will actually disadvantage the marginalized kids and teens its supposed to protect, around the same time that KOSA was dropped. Now it’s back with a vengeance, alongside a slate of laws that could enable unprecedented levels of surveillance and censorship. Concerned citizens should call their representatives and urge them to vote ‘No’ on these laws, but even if they aren’t successful this time, it’s clear that this fight won’t end as long as people are convinced that we need to “protect” kids by silencing all us.

“Like any moral panic, we are throwing away free speech and the autonomy of young people for a convenient safety narrative,” Philips said. “We’re kind of stuck in this conversation that social media is unilaterally bad for kids, but that’s not actually unequivocally true. For marginalized kids, for LGBTQ+ youth of color, for example, online communities are actually a huge indicator of mental health success. Because if you don’t live in an affirming household or community, then you turn to the internet.”

The tragic reality is that blocking kids from accessing information puts them in more danger, not less. One situation Philips posed to me that made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up is the idea that a 16-year-old in Texas, for example, could get pregnant and be denied abortion access—as well as information online about obtaining an abortion through other means, and even parenting the children they’re forced to have. The messy reality doesn’t match our idealistic assumptions about what limiting internet access for people under 18 will actually do.

As a healthy, well-adjusted queer adult who grew up online, I encountered both harmful and helpful things on social media—and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. The positive vastly outweighed the negative, no contest. And I truly fear for kids growing up without the same access to information outside their bubble. That’s the future that anti-LGBTQ conservatives want, and by weaponizing child safety rhetoric, they’re on the path to accomplishing it. As Philips pointed out and I’ve reported on over the years, many platforms have chosen to comply in advance and are already censoring vast swaths of content that isn’t harming anyone and can actually help people.

When it comes to Bluesky, an adolescent platform that could easily be wiped out by targeted government lawsuits, I don’t necessarily blame them for over-complying. But we’re going to keep moving backward without more support for the essential information infrastructure of the internet.